My 70 years with the Israel Exploration Society (1943–2013)

Joseph Aviram

I immigrated to Palestine in 1936 upon completion of my studies at the Tarbut Hebrew Teacher’s Training College in Vilnius (Lithuania). I was accepted to the Hebrew University, which granted me a Mandatory immigration permit and consequently, an exemption from being drafted to the Polish army. Aboard the ship Polonia I encountered a small notice concerning a shipboard lecture by Prof. Moshe Schwabe on the excavations at Beth Shearim, inviting all Hebrew speakers to attend. The lecture, accompanied by photographs, was fascinating and none of the 7 or 8 students attending had previously heard about this discovery. The lecturer spun the tale of how Alexander Zaid, a member of Hashomer (a pre-state Jewish paramilitary organization) by chance entered a cave and found a sarcophagus bearing Greek and Aramaic inscriptions and a drawing of a menorah on the wall. Zaid immediately alerted Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, his friend from Hashomer, who contacted his brother-in-law Benjamin Mazar, one of the only Jewish archaeologists at the time. Together they went to Sheikh Abreik, as the place was called prior to the surprising discoveries. They examined the caves by the light of candles and saw this Jewish necropolis with its inscriptions that include personal names. Prof. Schwabe explained that he was called upon to decipher the Greek inscriptions and showed us photographs of them.

During the mid-semester break from the university I saw an announcement by the Students’ Union of a planned tour of the Galilee led by Chaim Bar-Droma (who had recently published a book about the Negev) that would include a visit to Sheikh Abreik. I recalled Prof. Schwabe’s lecture and immediately registered for the tour. This was during the 1936–1939 Arab Revolt in Palestine, but the tour took could take place thanks to a lull during the Peel Commission’s stay in Palestine. When we reached Sheikh Abreik Bar-Droma invited Zaid, who appeared on horseback. From atop his mount he recounted how he and Moshe Yaffe, a local resident, entered the cave and then notified Ben-Zvi and Mazar. He told us that archaeological excavations were underway, but that they could not be visited. Some of us approached the area of the excavations and managed to peer into the cave. This was an exciting visit, complementing the shipboard lecture. We learned that a Greek inscription bearing the name Bishara had been found, the ancient name of Beth Shearim, hence the name change from Sheikh Abreik to Beth Shearim. The site had served as a major necropolis, including for Diaspora Jews seeking a final resting place in the Holy Land. Until 1940 four seasons of excavation were conducted there and numerous details appeared in the daily press and in scientific publications, in particular in the Bulletin of the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society. Exhibitions about the place were held in Palestine and in London. This excavation, the first large-scale archaeological project by a local Jewish archaeologist, raised considerable interest.

Following my arrival I worked as a school teacher in Talpiyot along with Moshe Shadmi, who was a member of the Wanderers Association and knew Mazar. One day Mazar asked him if he could recommend someone to work at the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society, as its secretary Mr. Friedrich had been drafted into the British army. Shadmi proposed that I speak with Mazar. I arrived at Mazar’s home at 32 Ussishkin St. in Jerusalem and was immediately served coffee. There I met Pesah Bar-Adon and Joseph Schweig, who were having a lively conversation about the Beth Shearim excavation in which both had participated—Bar-Adon as a volunteer and Schweig as photographer. Mazar informed me that my first task as part of my job replacing the Society’s secretary would be to copy a manuscript of the final report of the Beth Shearim excavations that Mazar had prepared. He added that there was an old Remington typewriter at the Society’s office, which was a room in his home. I asked why it was necessary to copy the manuscript, which appeared to be perfectly legible. He replied that the Bialik Institute had agreed to publish the book on the condition that a typed manuscript be submitted. I had never used a typewriter in my life but since I wanted the job, said I would take the typewriter home and begin to practice using it. I spent many nights on that typewriter and finally managed to produce a typed manuscript—imperfect but legible. Mazar provided me with the notebooks continuing the final report. He informed me that the rest of my duties were not up to him, and sent me to the Society’s treasurer, Zelig Weizmann for further instructions. I approached him with great awe and trepidation, thinking that he was Chaim Weizmann’s brother. While his wife, it turns out, was Chaim Weizmann’s sister, it was mere coincidence that Zelig shared the same family name. He first gave me the key to the Society’s mailbox and told me that it must be emptied three times a week and that correspondence must be answered to the best of my ability. In the event of a problem, I was told to ask him. Second, there were some 100 members of the Society who paid annual membership dues of ½ Egyptian pound, and the Society depended upon those contributions. The payment collector for the Society was a Mr. Eisland, the tax collector for the community in Jerusalem who did this on the side. He received a commission of 15% on each membership payment. You must find him, I was told, and arrange the payments and their transfer to the Society. As this was the Society’s main source of income, it was important to handle this effectively. While there was additional income from the sale of books, exclusivity had been granted the publisher Ruben Mass who, Mr. Weizmann informed me, he was planning to take to court for failure to remit the sales’ income to the Society over a period of many months. My monthly payment for this work was to be 1 pound, as it had been for my predecessor. I was told that there were not always funds in the kitty and it was reiterated that I must see to it that the funds collector make an effort to obtain all the membership dues, as it was unpleasant to have to remind such respected Society members as Ussishkin, Ben-Gurion, Ben-Zvi, and Sharett. I accepted these duties. I met with Mr. Eisland and we agreed on several matters. He described the difficulty collecting membership dues from important figures among the Society’s members. I managed the correspondence (of which there was very little) and that was my first job at the Society.

The Society’s conventions

I prepared for the meeting of the board of directors, held at the home of the Society’s president Prof. Leon A. Mayer on Abravanel St. in Rehavia. Despite the tensions created by World War II, the meeting was held at the end of November 1942. Though Rommel was at El-Alamein, the gateway to Egypt, the Society continued its activity, in contrast to the situation that prevailed during World War I, when the Society’s founders scattered abroad for fear of the Turkish administration. At that meeting I was introduced to the participants: Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, Moshe Schwabe, Shmuel Yeivin, Benjamin Mazar (originally Maisler) and Zelig Weizmann. Moshe Steckelis and Michael Avi-Yonah also attended that meeting. Mazar presented me as the replacement for the previous secretary. My name at the time was still Joseph Abramsky, however Ben-Zvi persisted in calling me Mr. Avrahami. After the report on activity was presented by Mazar and Yeivin, Steckelis and Avi-Yonah were invited to present their proposal. They stated that, now 30 years old, the Jewish Palestine Exploration Society was the realm of an elite. While its members included important public figures and intellectuals, it was not reaching a broad audience and particularly, neglecting members of the kibbutz movement, the moshavim and teachers, all hungry for information concerning all aspects of Land of Israel studies, including archaeological excavations. By expanding its scope, the Society’s financial situation would also improve. Their practical proposal was to hold conventions for Land of Israel studies with an open invitation to all those interested. Everyone present agreed that this was indeed necessary. If successful, expansion of the Society would be possible. The question of who would organize such an event arose. An experienced administrator would be required. Prof. Mayer proposed Dr. Bruno Kirschner as the appropriate person. A recent immigrant from Germany, he was in need of work and had organizational abilities. The treasurer asked how much his services would cost, to which Mayer replied: 25 pounds a year. The treasurer asked who would pay, as available funds were insufficient to cover this expense. Mayer promised to cover the cost. The next day I met with Dr. Kirschner. Even before the board reached its decision, he had prepared a detailed program, written entirely in German, as Prof. Mayer had reached an agreement with him prior to the meeting. Dr. Kirschner proposed calling the convention “The Week of the Hebrew Past.” Fortunately, I knew German and we fully cooperated with one another. The detailed program was passed on to all of the board members for comment and we began planning the convention.

The First Convention was held during Sukkot 1943 and included lectures and fieldtrips. To everyone’s surprise 300 people from around the country attended and it was truly a celebration. The event was publicized in all of the newspapers and a folder was prepared for each participant containing material about the conference schedule, lectures and events. This was later published as a book that aroused interest throughout the country. The Society treasurer Weizmann had died prior to the convention and the volume was dedicate to his memory. In light of the success of this conference the board of directors decided to make it a regular event, the main one in the country during the Sukkot holiday. It continued through the following decades.

The Second Convention for Land of Israel Studies was held in Tel Aviv and its topic was “To the Shore of Seas.” It too was a resounding success, with even more participants than the previous convention. Most participants became members of the Society, consequently improving its financial situation. Following Weizmann’s death, Dr. Yitzhak Ernst Nebenzahl (later to become Israel’s State Comptroller) was appointed as treasurer. He took great interest in the activities of the Society and even supported it in times of need.

The Third Convention was held in Haifa in 1945, sponsored by the Haifa Municipality. It was already a more sophisticated affair and included exhibitions. The theme was “Trade, Industry and Crafts in Antiquity” and the fieldtrips were held throughout the Galilee. This time over 500 participated, including the heads of the Jewish Agency, the Zionist Commission, the Jewish National Fund and many kibbutz members. Land of Israel studies groups of the kibbutzim organized transportation from all across the country.

These conventions were widely publicized, primarily thanks to numerous press articles. Consequently, the Society was approached by mayors of cities and regional councils proposing that future conventions be held in their jurisdictions, enabling us to pick and choose the most appropriate locations in terms of lecture halls and accommodations. The municipalities and regional councils offered every assistance and the conventions became regional celebrations.

The mayor of Tiberias invited us to hold the Fourth Convention in his city in 1946 and we chose the theme: “Land of Kinnerot.” A very rich program of lectures and fieldtrips was planned and all of the materials were published in a volume with this title. Tiberias filled with participants from all over the country and all of the hotels and hostels were filled to capacity. We were forced to accommodate some of the participants in kibbutzim in the area. Toward the middle of the convention it was announced that the situation in the country had taken a turn for the worse. The British declared a curfew in many areas due to clashes with their military. There was considerable tension and some of the participants feared that they would be unable to return home for the last day of the Sukkot holiday. I spoke with Prof. Eleazar Lipa Sukenik, who participated in the convention and lectured and guided at the Hammat Gader and Chorazim excavations. He contacted his son, Yigael Yadin, who then served as operations officer of the Hagana, to ask him if we should halt the convention. Yadin replied: “We don’t stop reading the Torah in the middle. Complete the convention and then return to your homes.” This was in the period leading up to the War of Independence and the situation remained tense until we knew that everyone had managed to return home safely. The Society’s activity then came to an almost complete standstill until the battles ceased. A small convention was then held in Jerusalem, the Fifth Convention. The main speaker was Abba Eban, who presented a talk about the political situation following the first ceasefire.

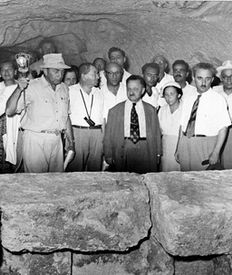

In 1950 Moshe Gobesman, who was active in the Tel Aviv branch of the Society, proposed utilizing the immigrants’ ship SS Komemiut to sail to Acco and hold the Sixth Convention there. The mayor of Acco at the time was Baruch Noy and the military governor was Rehavam Amir. Both were enthusiastic about this decision. Since there were no hotels in Acco, the mayor promised to accommodate some of the participants in private homes of Arab residents and others, as usual, in the various kibbutzim in the surrounding area as well as in Nahariya and Haifa. Approximately 500 set out on the ship from Tel Aviv. The guides during the journey along the coast were Yosef Breslavi, Yehuda Karmon and Zeev Vilnay. David Remez participated in that convention and aboard ship gave a talk on the Israeli merchant fleet. We arrived at Acco in the afternoon. In the evening the convention was opened by Prof. Mayer, president of the Society, who added greetings in Arabic for the benefit of the Arab participants. The guests of honor were Prime Minister David Ben Gurion and the Chief of Staff Yigael Yadin. They greeted those in attendance and gave lectures as well: Ben Gurion on the current situation and Yadin on the topic: “And why did Dan remain in ships?” Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, who always greeted at the convention openings, spoke of the Society’s activity. From Acco participants went on tours of the Galilee and returned to hear lectures in the evenings. The Jewish National Fund and its head, Joseph Weitz, were full partners in these conventions. He would always lecture on the newly created settlements in the vicinity of each convention.

The Seventh Convention was held in Tel Aviv during Sukkot of 1951. It was the second held in that city. It focused upon the excavations at Tell Qasile, where the third season of excavations directed by Benjamin Mazar had been completed.

The Eighth Convention was held in 1952 at Beth Yeraḥ on the shore of the Sea of Galilee. Ohalo House had already been constructed and the convention was held outside, on a lawn specially prepared by members of Kibbutz Kinneret. The convention had numerous participants, including Nahum Slouschz, Nelson Glueck, Hans Gustav Güterbock, members of the Beth Yeraḥ archaeological expedition and as always, Yitzhak Ben-Zvi, still active on the Society’s board of directors. He focused in his speech on the personality of Berl Katznelson, in whose memory Ohalo House was constructed. The archaeological excavations at Beth Yeraḥ had been underway for a few years under the direction of Benjamin Mazar, Michael Avi-Yonah, Pesah Bar-Adon and Moshe Steckelis.

The Ninth Convention was devoted to the theme “Land of the Negev” and was held at Beersheva during Sukkot 1953. Here too, lacking hotels the municipality, under the leadership of its Mayor David Tuvyahu, made arrangements with residents to host some of the participants in their homes. The convention also inaugurated the Keren Cinema hall, which had just been constructed, where the lectures were presented. The guest of honor at this convention was Prof. William Foxwell Albright and Yitzhak Ben-Zvi participated as the president of Israel. David Ben Gurion, who had recently moved to Sde Boqer, participated in the convention and an interesting discussion ensued between him and Albright concerning the Exodus from Egypt and whether the 60 “ריבוא” participating in the Exodus from Egypt were 60,000 or 600,000 individuals. Participants made fieldtrips around the Negev and visited, among other places, Avdat, Shivta, Halutza and Nizzana.

The wanderings of the Society office

Shortly after I entered the Society’s office in Mazar’s home, Dina, his wife (and Ben-Zvi’s sister), approached me requesting that I vacate the premises because their son was already grown and needed a room of his own. This was no simple matter: Where does one find an alternative room? Yosef Schweig came to the rescue and told me that in his flat on Bnei Berith Street there was an empty, unused room. He offered it to the Society free of charge. What I found was a dark room with an earth floor, damp and lacking cupboard or shelves. We ordered a carpenter who, over the course of a few days, constructed some temporary fixtures in the room and we moved the few things from the office at Mazar’s house: some books and a few issues of the Bulletin. I hired a porter with a donkey cart and moved everything to our new office. I told Schweig that there was no need for a desk as I would surely not be sitting there, nor would electricity be necessary as nobody would be going there in the evening. Thus it was for about a year and a half. At the end of World War II in 1945, Schweig asked me to vacate the room: a friend of his had been released from the army due to illness and needed a place to live. The soldier, Dov Rozhansky, happened to be an acquaintance of mine from the university. Another miracle occurred and Dr. Haim Zeev Hirschberg, a friend of Prof. Mayer, arrived with the Teheran Children (child refugees from Poland whose flight from the Nazis took them to Teheran), rented a large flat on Shamai St. and had an extra room that he was willing to sublet. I took the room, which was quite suitable, and again, with a donkey cart, moved office. Shortly afterward we had to leave that room and fortunately found a two room flat at 16 King George St. Meanwhile, the Society’s financial situation had improved and we could afford to pay the rent of 1.5 pounds a month. At that flat we employed a student part time, Mr. Isaac Lombrozo, who later became a lawyer and then honorary treasurer of the Society, a position that he holds to this day. Some years later Bank Leumi, which was in the same building, expanded and asked that we leave the two rooms in exchange for a larger key-money premises. We managed to move to a three room flat at 3 Shmuel Hanagid St. where we remained for 25 years until we further expanded and moved to our present 5 rooms at 5 Avida St. with 8 employees. The growth of the Society is reflected in these moves: more rooms, more employees, more activity and a larger budget. This growth was measured in the number of archaeological excavations, publications and the general dissemination of Land of Israel studies to the public.

Activity of the Society

In the 1940s we managed to publish the Bulletin, despite the difficulty in obtaining paper during World War II. We held meetings of the Archaeological Circle on an almost regular basis.

During this period the Society’s activities and the discussions of its board of directors mainly concerned the conventions, the publications and matters that arose at the time of the founding of the State of Israel and the end of the Mandatory Department of Antiquities’ activity. In the newly formed State, the Society was the only organization dealing with the exploration of the country and its archaeology and we acted as a source of information for the government and other bodies. The first excavation permit issued by the government, signed by the first Minister of Labor Mordechai Bentov, was for the Society to excavate at Tell Qasile under the direction of Benjamin Mazar. The excavations were sponsored by Tel Aviv Mayor Israel Rokach and funded by the municipality. They continued for three seasons. The government approached the Society to propose a building to house the Israel Department of Antiquities and this was cause for numerous discussions. Shmuel Yeivin was proposed as the director of the department. For the time being, the Department of Antiquities was adjunct to the Ministry of Education. The first education minister, Prof. Ben-Zion Dinur, assigned the Society the task of preparing a broad research plan, including an archaeological survey of Israel and proposals for a program of archaeological excavations. A special committee was created for that purpose.

Following the creation of the State, Ben Gurion wrote the Society proposing that its name be changed from Jewish Palestine Exploration Society to Israel Exploration Society. This proposal was immediately accepted at a meeting of the Society’s Council.

With the expansion of the Society and the increase in its membership and supporters, mainly thanks to the conventions which ultimately hosted over 1,000 participants, financial possibilities grew and the board of directors decided to expand its range of publications beyond the Bulletin to include a series titled Eretz-Israel, an annual that would include articles too long for presentation in the Bulletin. The first volume in the series was dedicated to the memory of Zalman Lif who had been chairman of the board of directors and had made a major contribution to the development of the Society. Very soon this publication became a Festschrift series honoring individuals active in the Society. Thirty-four volumes have been published to date, each dedicated to someone who played a key role in the Society’s development and activity.

During this period there was considerable demand to establish branches of the Society with ongoing activities including lectures, tours and volunteer opportunities for excavation projects. Thus, in addition to the extant Tel Aviv-Jaffa branch that dated to the time of the Society’s founding, branches were opened in Haifa, Tiberias, Hadera, Binyamina, Ben Shemen and Holon. These branches were short lived as their existence depended upon enthusiastic individuals. Furthermore, the Society was unable to provide the lecturers and guides needed and the branches’ activities eventually ceased. The Land of Israel studies section of the kibbutzim, on the other hand, remained active and provided numerous volunteers to excavations, however it also eventually ceased to exist as the older generation disappeared.

The 1950s and 60s

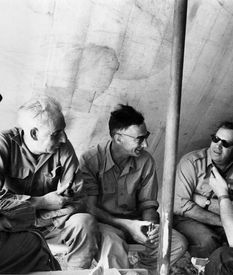

In 1953 Shmaryahu Guttmann of Kibbutz Naʿan approached me and informed me that during the last expedition of a youth movement to the Judean Desert and Masada, in which he was involved, one group, using ropes, had succeeded in reaching places of difficult access at Masada. He brought numerous photographs and drawings of buildings, including fallen columns and other remains not seen previously. He proposed inviting all those interested so that he could present a lecture accompanied by slides. I immediately approached Prof. Mazar, who was already president of the Hebrew University, and told him of these discoveries. He proposed an evening on Masada at his home. Michael Avi-Yonah, Nahman Avigad, Yohanan Aharoni, Munya Dunayevski and several others were invited. Mazar had told Minister of Education Dinur about the discoveries and he also attended the meeting. Guttmann presented all of the material they had been able to document. The discoveries made a considerable impression and the minister proposed planning a detailed survey involving the participation of scholars dealing with the relevant periods. Given the inherent difficulties in such a project, including lack of convenient access and supplying basic necessities to those working at the site, it was agreed that only the army would be capable of handling the logistics. The chief of staff at the time was Moshe Dayan, who was enthusiastic and assigned Rehavam Zeevi (Ghandi) to examine the possibilities. Ghandi prepared a complete and detailed plan. The survey could only be carried out with assistance from Bedouins and using mules as transport. Food and water could only be carried up the mount via the Snake Path and it would have to be prepared to accommodate the passage of mules. I was assigned the task of coordinating the campaign and a man named Captain Magen was my contact person in the IDF.

The campaign took place in 1955. We recruited approximately 20 students to the expedition headed by Avi-Yonah, Avigad, Aharoni, Guttmann and Dunayevski. A photographer and a surveyor also participated. There were 30 participants in all. The IDF provided tents, tools and food. Water was transported daily from the springs at ʿEn-Gedi. All of the equipment and supplies were carried close to the summit of the mount daily by mules along the Snake Path and from there, raised with ropes by the volunteers. The work was extremely difficult but there was a major effort and enormous enthusiasm to discover as much as possible. The results of the 16-day campaign were published in book form as the Masada Survey. A meeting was convened with the participants to summarize and propose future activities, the aim being an excavation campaign at the site. Given the conditions in which the survey was carried out, it was concluded that excavations at the site would not be possible without coordination between government bodies and military assistance. It was decided to discuss the matter with Yigael Yadin, who had been released from his military duties and was now a lecturer at the Hebrew University. Guttmann, Aharoni, Yehuda Almog, the head of the Tamar Regional Council, and I were received by Yadin and presented him with the facts. He expressed his regrets, stating that he was already committed to a four-year excavation program at Tel Hazor, the largest biblical-period tell in Israel. This, he explained, was how he wanted to begin his archaeological career. This appeared to put an end to plans for an excavation at Masada.

Yadin gathered all of the archaeologists in the country and invited them to participate in the Hazor excavation. He regarded this excavation as the ultimate archaeological field school. Participants included Yohanan Aharoni, Ruth Amiran, Jean Perrot, Trude Dothan, Moshe Dothan, Munya Dunayevski, Claire Epstein and senior students including Ephraim Stern, Moshe Kochavi, and Amnon Ben-Tor, among others. Some 250 workers participated in the excavation as part of a Labor Ministry initiative to provide employment. Upon conclusion of the Hazor excavation in 1960, we returned to Yadin concerning the Masada project, but the Judean Desert campaign then took precedent.

Through the 1950s there was considerable activity at the Society. Prof. Mazar was elected president and rector of the Hebrew University and could not devote much time to the Society. Zalman Lif, chairman of the board of directors, had died; Shmuel Yeivin, director of the Department of Antiquities, proposed ending the Society’s activity entirely. In his view all archaeological matters should be in the hands of the Department of Antiquities and contact with the public handled by the Antiquities Trustees circles. This view aroused considerable anger among other Society board members, foremost among them its president, Prof. Mayer. Meanwhile, Yadin, was selected as chairman of the Society’s board of directors. Aharoni and Ruth Amiran had earlier resigned from the Department of Antiquities, when Yeivin refused them leave of absence to participate in the Hazor excavation. Relations between the Department of Antiquities and the Society were thus tense. Rumors circulated that Yeivin was negotiating with Tel Aviv University to establish a department of archaeology there. Meanwhile, in Jerusalem a search for candidates for the position of director of the Department of Antiquities had begun. Abraham Biran was selected, having returned from service with the Foreign Ministry as consul in Los Angeles. After careful consideration and with numerous supporters, he agreed to accept the job. He was also elected to membership on the Society’s board of directors.

In the early 1950s efforts were underway to find a replacement for the Palestine Archaeological (Rockefeller) Museum, which lay across the armistice line in Jordan. Prof. Mayer drafted a memorandum to the government outlining the need to build a museum in the Jewish half of the city. Signatories to this memorandum included Teddy Kollek, Mazar, Yadin and Yeivin. Early on it became clear that it must be a museum of archaeology and art, as the Bezalel Museum was too small to hold its entire art collection. The memorandum reached Ben-Gurion who summoned Kollek, then head of the Prime Minister’s Office. He stated that such luxury had no place in the midst of the mass immigration and rationing prevailing at the time. Kollek reassured him that they were not asking for money, but only a piece of land for the building, which would be erected with philanthropic contributions. Thus the campaign began and in 1965 the Israel Museum and Shrine of the Book were inaugurated.

In 1960 David Noel Friedman approached Yadin, having arrived from the Jordanian half of divided Jerusalem, and told him that Bedouins were circulating in the Old City selling scroll fragments to tourists for $10. Friedman said that they had questioned the Bedouins and it emerged that all of this material came from excavations carried out by the Bedouins in Wadi Seyyal (Naḥal Ẓeʾelim) on the Israeli side of the border in the Judean Desert. This news alerted Yadin who, like his father, was extremely interested in ancient scrolls. He immediately informed Ben-Gurion, who in turn notified then Chief of Staff Haim Laskov. Laskov felt that rather than repeated minor expeditions, a comprehensive and thorough campaign was now called for. First Aharoni went with a group of volunteers to Naḥal Ẓeʾelim, assisted by the army, to verify that the rumors were true. They located a cave containing remains of Bedouins excavation, including several scroll fragments and other finds from the time of the Bar-Kokhba Revolt. It was then decided to mount a major project. The army put a helicopter at our disposal and we organized several patrols to locate caves to be examined and encampment sites for the expedition. I was given the responsibility of coordinating the campaign and liaison between the various bodies involved: the army, the volunteers, the press and participating institutions. Avraham Yaffe, chief of the Southern Command, was put in charge of the entire operation. The area was divided into four sectors/camps. The heads of these were Aharoni, Avigad, Bar-Adon, and Yadin. The army created the camps and assigned Golani Brigade units to protect them and provide assistance. The center was at Camp C where I was based with telephone links to the other camps. I approached the Land of Israel Studies Section of the Kibbutz Movement and asked for volunteers who, as usual, were eager to participate. There were so many applicants that we had to hold a selection lottery given the limited capacity of the camps. Numerous students also volunteered and were divided among the camps. The results of this campaign, conducted in 1960 and 1961, were first published in Hebrew in the Bulletin, later in English in the Israel Exploration Journal, and subsequently as a four-volume scientific report.

I imagine that Yadin’s tremendous success in the Cave of the Scrolls led him to rethink the proposed Masada excavation. In 1963, while he was on sabbatical in London, I received a telephone phone call from him asking if I could come to him in London for a few days. There he informed me that he had decided to embark on the Masada excavation. In effect, everything was already in place for this project. Yadin had obtain contributions from his friends in London and had reached an agreement with the prestigious Observer newspaper. This was the first time that volunteers from abroad would be enlisted to participate in an archaeological project in Israel and the newspaper’s main role was to publicize the expedition worldwide in order to attract such volunteers. Yadin’s condition was that I work together with him on this project. Carmela Yadin, his wife was put in charge of communicating with and making the necessary arrangements for the volunteers. In the pre-computer age, she developed methods to organize the thousands who applied and did a fine job. All aspects of this project, carried out in 1964–1965, are covered in Yadin’s popular book Masada, which was published in several languages. Today, decades later, Masada is one of the most frequented archaeological sites in Israel, with thousands of visitors from around the world.

When I visited Yadin in London he showed me a scroll fragment and after swearing me to secrecy revealed that an agent had told him of a dealer in Israel who had the longest scroll found to date (9 meters long) and had shown him a fragment proving its authenticity. The dealer was asking $100,000 for the scroll. Meanwhile, as an advance to continue the transaction he wanted $10,000. Yadin received the advance amount from Leonard Wolfson and paid the agent. Despite the lack of guarantees, Yadin and the donor had decided that the risk was worth taking for the possibility to acquire the scroll. The man disappeared with the money leaving no trace and years passed. Yadin was nearly certain that the scroll was held by a well-known Bethlehem scrolls dealer, Khalil Iskander Shahin, better known as Kando. During the Six-Day War the army sent several officers to Kando’s home and feeling threatened, he had shown them a scroll hidden in his basement in a cardboard box and had given it to the officers. The scroll reached Yadin who sent it to the Israel Museum’s conservator, Dodo Shenhav, to be carefully unrolled. I was invited to see it, spread out over the floor of Shenhav’s flat, and it turned out that the piece Yadin had obtained previously was indeed a missing piece from that scroll. The State of Israel finally paid Kando $105,000 and the scroll is in the Shrine of the Book. Yadin published it at the Israel Exploration Society in a three-volume set in Hebrew and English titled The Temple Scroll. Yadin worked on that publication for nearly 10 years and became so involved in it that the publication of the Masada and Judean Desert Expedition final reports were postponed. It was only after Yadin’s death that the Israel Exploration Society managed to publish most of his scientific legacy, work that continued for over 30 years.

The Six-Day War opened Jerusalem to research and archaeological excavations. Jerusalem Mayor and Israel Exploration Society board member Teddy Kollek demanded that excavations begin immediately. Mazar began to excavate along the southern wall of the Temple Mount in what came to be called the Western Wall excavations. Avigad began excavations in the Jewish Quarter and later Yigal Shiloh dug at the City of David. These excavations continued over a period of some 20 years. All three of these archeologists died and the final reports of their work have been and continue to be published by individuals who participated in the excavations as assistants or area supervisors.

For the first 100 years of its existence the Israel Exploration Society underwent numerous transformations. Major changes occurred in the composition of its membership and the nature of its activities. I served the Society for over 70 years and remain the only surviving member of the Society’s generation of the 1940s, 1950s and 1960s.

Marking 75 years of its existence the Israel Exploration Society was awarded the Israel Prize in 1989 for its contribution to society and the State. I had the honor of receiving this in the Society’s name from the heads of State at the Independence Day ceremony that year.